By STEPHEN KAPAMBWE –

SHE was barely 18-years-old when poverty forced her relatives to marry her off.

The marriage did not work.

At the age of 23, orphaned Tamara (not her real name) is yet again faced with prospects of being married off for the second time.

She fears this second marriage will curtail her dream of finishing Grade Seven.

Fathered by a man she never knew, Tamara lost her mother at a tender age before she was taken up by relatives in Chipata.

She has since lost two children born out of wedlock.

Hers is a story of a traumatic loss of adolescence.

Like many girls that have been lost to the vagaries of child, forced and early marriage, Tamara suffers in silence, knowing that her desire of getting a descent education and gain control of her life will forever be a pipedream.

According to Girls Not Brides, Zambia has one of the highest child marriage rates in the world with 42 per cent of young women aged 20-24 years married by the age of 18.

This rate has not changed since 2002.

The rates of child marriage vary from one region to another, and are as high as 60 per cent in the country’s Eastern region.

Girls Not Brides says girls who are affected by poverty, lack of education and longstanding traditional practices that discriminate against girls and women, are most vulnerable to child marriage.

For example, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) found that 65 per cent of women aged 20-24 with no education and 58 per cent of the women with primary education were married at the age of 18 compared to only 17 per cent of women with secondary education or higher.

Visiting University of California Professor Louise Fox has since warned that African countries like Zambia risk having uneducated and subsequently more unemployed young people as a result of society’s failure to arrest child marriages.

She said as a result of early marriages that push girls out of school, the girls not only fail to develop cognitive and behavioral strengths they need in adulthood to navigate the challenges of life, including those related to a sustainable livelihood. But they also fail to pass on such skills to the next generation.

In other words, early marriages will eventually create a generation of uneducated mothers who equally fail to pass on cognitive and behavioural strengths required in life to the next generation.

Professor Fox said this when she addressed the recent African Economic Research Consortium (AERC) bi-annual conference at Inter-Continental hotel in Lusaka.

She said the problem of early marriages and early child birth posed a big challenge for young African females.

“For young women, the pathway from school to work can be especially treacherous. As they navigate the school-to-work transition, they may encounter social norms that limit their agency and their employment choices.

“For females, the school to work transition is particularly challenging as it occurs at the same time as family formation,” she said.

Professor Fox described the problem of child marriages in terms of their impact on girls’ acquisition of cognitive skills (like numeracy and literacy) as very serious.

She quoted a report by the Population Council that said in Africa, “adolescence is a time of widening opportunities for boys, but constricting (narrowing) opportunities for girls,” she said.

“By the age of 25, nearly 80 percent of women in Africa have married and given birth. This transition happens later among men. While more than half of all women are married by the age of 20, the majority of men are likely to remain unmarried before the age of 25, and marry only in their late twenties or early thirties,” she said.

She said the education problem for girls, in terms of the loss of cognitive skills and society’s failure to allow them to use their adolescence to widen their opportunities, is very serious.

She said adolescence should constitute learning about the world and how to respond to opportunities. But in the African scenario, this is when most of the girls drop out of school.

As a result, the girls do not build up their cognitive skills and because of that, they may equally fail to pass on such skills to the next generation.

Professor Fox said ordinarily, time in adolescence which could be spent acquiring job-related skills is instead spent trying to find funds and finish up school, and then searching for the holy grail of a high paying wage job which they do not find.

She believes factors contributing to this difficult transition develop early, even before adolescence.

This means that the solutions-policies and programs-also need to start early, before the young people who are targeted by such interventions leave school.

But she warns that for African females, the interventions need to start before onset of fertility, to help them and those who care for and nurture them make choices which open opportunities for their own development.

“This will have a major long term payoff for society, as it will lead to higher human capital in the young women’s generation, and help improve reproductive outcomes in future generations,” she said.

Girls Not Brides, a global partnership of civil society organizations committed to ending child marriage and enabling girls to fulfill their potential, says in 2013, the Government in Zambia launched a nation-wide campaign to end child marriage.

The campaign was spearheaded by the ministry of Chiefs and Traditional Affairs.

It sought to draw attention to the dangers of child marriages and to encourage communities to delay marriage for their daughters.

The launch of the campaign was followed by a symposium on child marriages, which brought together key stakeholders – including various ministries, traditional leaders, civil society organisations, young people, media institutions and United Nations (UN) agencies – to explore ways to collaborate efforts towards arresting child marriages in the country.

The Zambia Government is also taking steps to put the problem of child marriages at the forefront of the regional and international agenda.

In September last year, Zambia co-sponsored with Canada the first UN General Assembly resolution on child, early and forced marriage.

Zambia has since won global acclaim for spearheading the fight against child marriages.

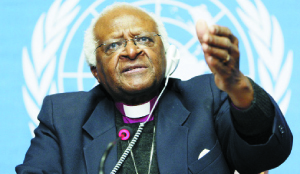

On September 15, 2014, Nobel Peace Prize laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu and Princess Mabel of Orange-Nassau of the Netherlands visited Zambia to learn about the country’s best practices in combating child, early and forced marriage.

Princess Mabel and Archbishop Tutu met and exchanged ideas with Zambian Government officials and other stakeholders on the fight against child, early and forced marriage.

Princess Mabel is the chairperson of the board of trustees of Girls Not Brides, a global partnership of more than 300 civil society organisations campaigning to end child marriages.

Princess Mabel was the first chief executive officer of The Elders-a group of eminent global leaders brought together by the late South African statesman Nelson Mandela to promote peace and human rights – chaired by Archbishop Tutu.

The Zambian Government has received international applaud for its best practices in combating child, early and forced marriage.

Partnership of chiefs, civil society and the Government is one effective campaign being used to fight child marriages in Zambia.

Traditional leaders support the campaign against child marriages and most of them have banned the practice in their chiefdoms.

Some chiefs are even involved in retrieving young girls from forced marriages.

The traditional leaders and their subjects report parents that marry off their young girls to the police for prosecution.

Chiefs, civil society organisations and Government officials have become instrumental in encouraging parents, and guardians, to prioritise education of girls.

But poverty and entrenched cultural practices still expose underprivileged girls like Tamara to early marriages that effectively stop their childhood dreams of acquiring a descent education to lead productive lives.

Although cases of child, early and forced marriage could mean little in light of current demographics, their effect on posterity could be more telling than previously thought.