IN last week’s edition of our column we noticed that poets live in communities and interact with real people struggling with innumerable issues of life. And that actually the greatest resource for their work is all that goes on around us. But we also found out that unlike many of us, they perceive things far deeper than we do and reconstruct every day occurrences in finer and more interesting pieces that appeal to our senses much more dearly.

IN last week’s edition of our column we noticed that poets live in communities and interact with real people struggling with innumerable issues of life. And that actually the greatest resource for their work is all that goes on around us. But we also found out that unlike many of us, they perceive things far deeper than we do and reconstruct every day occurrences in finer and more interesting pieces that appeal to our senses much more dearly.

We saw, for example, how Gabriel Okara, the Nigerian poet and novelist, was able to reconstruct daily expressions among

acquaintances and friends: “Feel at home,” “It has been nice to meet you” and “Come again,” in a way that makes the poem, “Once upon a time” intricate and charming.

As we progress, I would like to note another interesting aspect of poetry—short poems packed with great themes and loft thoughts for our mental polemics. In fact, J. P. Clarks’ poem which we quoted in last week’s edition, “Stream side exchange,” is a case in point.

We are mesmerized by its simplicity and innocence and aptly identify ourselves in the Child-Bird conversation that displays great

metaphysicalproportions.

CHILD:

River bird, river bird,

Sitting all day long

On hook over grass,

River bird, river bird,

Sing to me a song

Of all that pass

And say,

Will mother come back today?

BIRD:

You cannot know

And should not bother;

Tide and market come and go

And so has your mother.

‘Stream side exchange’ firstappeared in a collection of poems by

Clark, “A reed in the tide,’ the tile of which is familiar to all of

us who have lived near streams or ravines crisscrossing our

geographical land scape. Reeds grow tall and straight and they are a resource for a craftsmen and dealers in baskets and mats.

Apparently, this is where Clark’s bird sits ‘all day long’ on a ‘hooked’ grass bowed by the bird’s weight, a kind of detail that a casual reader can easily miss. There is a sense of urgency in the Child’s search for the mother expected to return home ‘today,’ although the Birds response is heavy and haunting as there is no telling when her return is imminent,suggesting that life is a passing phenomenon; that it is like ‘markets’ where goods pass from hand to hand–so is life, it is slippery and transient. This is a short and seemingly simple poem but its meaning is transcendent.

Let us now turn to another poem by the same Poet called, ‘Ibadan’:

Ibadan,

Running splash of rust

And gold—flung and scattered

Among seven hills like broken

China in the sun.

There are nineteen words in this poem but its motif is far broader, richer and deeper than what meets the eye. Clark’s use of imagery in this poem is startlingly amazing.

It is, as the title suggests, a poet’s panorama of the city of Ibadan where he spent years studying at the University bearing the same name in the western part of that most populous country of Africa, Nigeria.

In the poem, Clark’s imagination runs riot, evoking powerful images of beauty and poverty, orderliness and recklessness all lying side by side. Worthy of note is Clark’s economy and conciseness of language and a careful choice of words: ‘running,’ ‘splash,’ ‘flung,’ and ‘broken.’

These are not words used for the sake of it; they set the mood and texture of the poem. In them we see a city imprecisely planned, a mixture of splendor of ivory tower University edifices, sprawling slums and all –‘splashed’on seven hills perhaps a resemblance of the seven hills of the ancient city of Rome.

Clark’s indention of the second line starting with ‘running’ is not a statement in error; it is a creation of a mood of the poem in its search and understanding of the expansivecity, as the poet describes it of ‘gold’ and ‘dust.’

China sits pretty creating a splendid picture of the University architectural sublime beauty. Clark’s poem makes your imagination run with his in search of meaning; this is the stuff that great poetry is made of and all apprentices of poetry have an opportunity to take lessons from him.

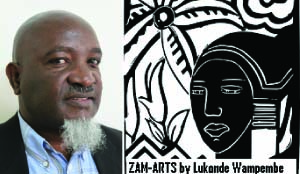

In our discussion of poetry and how it is crafted we have mostly looked at two accomplished poets from West Africa, namely, Okara and J.P. Clark and this is intentional because in this column we will only expend our creative energies on appreciated works of art rather than settle for mediocrity that we are normally wont to reading in our time.

Getting closer home, here is a short poem which I wrote some time back on my several visits to South Luangwa National Park with some children from communities in Chipata. Named ‘The Hippopotami,’ the poem was read at an International Conference of writers in 2005, Kampala, Uganda—courtesy of the British Council that sponsored the trip for the young writer, the late Namuchimba and me.

A hippo—

In the borrowed boots of an elephant

An unfinished tail—

Like a finished village broom

Hanging between wrinkled thighs.

This poem consists of only twenty words. I was inspired by the game viewing we undertook one bright morning on the banks of Luangwa River— where there is a huge concentrated crop of hippos— perhaps the largest in this part of Africa, wadding in the murky waters of the river.

Straddling on broken twigs, I was intrigued by the hippos’ ‘boots,’ sinking in and out of the mud and— sometimes running off from our stare, they would disappear in the thickets.

On the surface of it, these are just beasts of the wild but the poet’s eye sees more applying the intensity of imagery and the economyof language expression.

In the second line, the poet likensThird World countries to a‘hippo’ with ‘borrowed boots’ of ‘an elephant.’ So, what is an ‘elephant’ in this poem? What else can the reader see in it?